Reprinted with permission from Forbes.com where Jim is a regular contributor.

For more than twenty years, I have advocated “Pay Taxes later, except for the Roth.” This applied in the accumulation stage when you are accumulating money for retirement, the distribution stage when you are deciding which assets to spend first, and even in the estate planning stage. I always said there were some exceptions to this bedrock foundational principle, but this was a great starting point for general advice.

Since the SECURE Act became effective on January 1, 2020, the exception to this general rule became much bigger for many IRA and retirement plan owners.

What follows comes from our newest book, Retire Secure for Professors, which has great information for all IRA owners. Non-professors could skip the chapters on TIAA and still get a lot of value from the book.

Following is an excerpt from Retire Secure for Professors:

The next big question is: In what order should you spend the money you have saved for retirement? Subject to exception, you should spend your after-tax dollars before your retirement plan or IRA dollars.

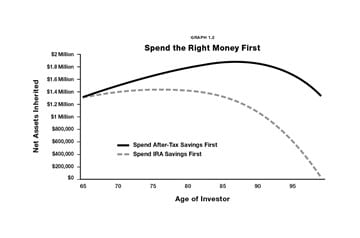

Please look at the graph that follows. Both couples start with the same amount of money in a regular brokerage account—which I refer to as after-tax dollars—and in their retirement plans. The graph below indicates, subject to exceptions, that most readers should spend their after-tax dollars first and then IRA and retirement plan dollars. The solid line shows what happens to the first couple who spend their after-tax dollars first and withdraw only the minimum from the IRA when they are required to (more on RMDs in the next section). They pay-taxes-later. The dashed line shows what happens to the second couple who spend their IRA first. They pay-taxes-now.

Graph 1.2: Spend the Right Money First*

*Detailed assumptions can be found at https://paytaxeslater.com/graph/

*Detailed assumptions can be found at https://paytaxeslater.com/graph/

The only difference between the dashed line and the solid line in this graph is that the first couple retained more money in the tax-deferred IRA for a longer period. Even starting at age 65, the decision to defer income taxes for as long as possible gives the first couple an extra $625,591 if the couple lives to age 87. If one of them lives longer, paying taxes later will be even more valuable to them.

Subject to exception, I generally prefer you not spend your Roth IRA dollars unless there is a compelling reason. The Roth IRA grows income-tax-free for the rest of your life, your spouse’s life, and for 10 years after you and your spouse are gone. In addition, there is no required minimum distribution for you or your spouse with a Roth IRA.

So, in general, the last dollars you want to spend are your Roth IRA dollars. Of course, there may be times when it makes sense to spend your Roth dollars before other retirement plan dollars if it keeps you in a lower tax bracket.

That said, subject to exceptions, you and your spouse will realize a benefit by deferring the income taxes due on your retirement plans for as long as possible and generally hold off on spending your Roth IRA. And with the SECURE Act now part of the law, your children, and grandchildren (subject to some exceptions for minor children, people with disabilities, and other exceptional factors) will have to pay income taxes on the Inherited Traditional IRA within 10 years of your death.

A New Wrinkle in our Bedrock Principle

Since the passage of the SECURE Act, adhering to the pay-taxes-later rule in the distribution stage might not always be the best advice. With income tax rates likely on the rise, for some professors, it might make more sense to plan for a transition from the taxable world (most TIAA accounts, IRAs, retirement assets, etc.) to the tax-free world (Roth IRAs, 529 plans, life insurance, your children’s Roth IRAs, etc.). To get the best result, it is best to analyze each situation on a case-by-case basis.

In short, the SECURE Act dramatically accelerates the taxes on your retirement plan after your death. For your children, losing the lifetime stretch on an inherited retirement account can carry a huge tax burden.

One reasonable strategy for some professors with significant IRAs and retirement plans who will not likely spend all their money is to make taxable withdrawals from the retirement plan and/or IRA, pay the tax, and then gift the net proceeds. The gift could be invested in something that grows tax-free like a 529 plan, your children’s Roth IRAs, life insurance, etc. That serves the purpose of getting some money out of your estate and allows tax-free growth for your children.

As a result, for many faculty members, an earlier transition from the taxable world to the tax-free world might work better than the standard rule of “pay taxes later.”