When planning for retirement, one of the most important decisions investors face is choosing between a Roth IRA vs Traditional IRA. While both accounts are designed to help you build long-term savings, the way each is taxed can significantly affect future growth, retirement income, and overall purchasing power. Understanding how tax-free growth compares to tax-deferred growth is critical, especially as income levels, tax brackets, and retirement timelines evolve. This is why the Roth IRA vs Traditional IRA comparison continues to be one of the most searched and debated topics in retirement planning.

The analysis below draws from Retire Secure! for Professionals and TIAA Participants by James Lange, a nationally recognized CPA, attorney, and retirement planning expert. Throughout the book, Lange explains the long-term advantages of a Roth IRA, particularly the impact of tax-free compounding over time. These Roth IRA benefits can become especially meaningful when future tax rates, required minimum distributions, and estate planning considerations are factored in. The section that follows explores these ideas in depth, showing how Roth IRAs and Traditional IRAs perform under different tax scenarios and why, in many cases, tax-free growth may offer a lasting advantage.

What Makes a Roth IRA So Great When Compared with a Traditional IRA?

The advantages of compounding interest on both tax-deferred investments and on tax-free investments far outweigh paying yearly taxes on the capital gains, dividends, and interest of after-tax investments. As you saw in Chapter 2, you are generally better off putting more money in tax-deferred and tax-free accounts than in less efficient after-tax investments. Remember that with regular after-tax investments, you must pay income taxes on annual dividends, interest, and, if you make a sale, on capital gains.

The Roth is always a much better choice than the nondeductible IRA. You do not get a tax deduction for either, but all the money in the Roth IRA will be tax-free when it is withdrawn. The growth in the nondeductible IRA will be taxable.

The advantage the Roth IRA holds over a Traditional IRA builds significantly over time because of the increase in the purchasing power of the account. Let’s assume you make a $6,000 Roth IRA contribution (not including the $1,000 catch-up contribution if over age 50). The purchasing power of your Roth IRA will increase by $6,000, and that money will grow income tax-free.

On the other hand, let’s assume you contribute $6,000 to a deductible Traditional IRA and you are in the 24% tax bracket. In that case, you will receive a tax deduction of $6,000 and get a $1,440 tax break (24% × $6,000). This $1,440 in tax savings is not in a tax-free or tax-deferred investment. Even if you resist the temptation to spend your tax savings on a nice vacation and put the money into an investment account instead, you will be taxed each year on realized interest, dividends, and capital gains. This is inefficient investment growth.

The $6,000 of total dollars added to the Traditional IRA offers only $4,560 of purchasing power ($6,000 total dollars less $1,440 that represents your tax savings). The $1,440 of tax savings equates to $1,440 of purchasing power, so the purchasing power for both the Roth IRA and the Traditional IRA are identical in the beginning. However, in future years, the growth on the $6,000 of purchasing power in the Roth IRA is completely tax free. The growth in the Traditional IRA is only tax-deferred, and the $1,440 you invested from your tax savings is taxable every year.

One of the few things in life better than tax-deferred compounding is tax-free compounding.

Traditional IRA, the tax savings you realize from a Traditional IRA contribution are neither tax-free nor tax-deferred. When you make a withdrawal from your Traditional IRA, the distribution is taxable. But when you (or your heirs) make a qualified withdrawal from a Roth IRA, the distribution is income-tax free.

Should I Contribute to a Traditional Deductible IRA or a Roth IRA?

As stated earlier, a Roth versus a nondeductible IRA is a no-brainer: if given the choice, always go for the Roth. But for those individuals with a choice between a Roth IRA (or work retirement plan) and a fully deductible IRA (or work retirement plan), how should you decide? The conclusion is, in most cases, the Roth IRA is superior to the deductible IRA (and nonmatched retirement plan contributions like 401(k)s).

To determine whether a Roth IRA would be better than a Traditional IRA, you must take into account:

- The value of the tax-free growth of the Roth versus the tax-deferred growth of the Traditional IRA including the future tax effects of withdrawals.

- The tax deduction you lose by contributing to a Roth IRA rather than to a fully deductible IRA.

- The growth, net of taxes, on savings from the tax deduction from choosing a deductible Traditional IRA.

In most circumstances, the Roth IRA is significantly more favorable than a Traditional IRA. (A number of years ago, I published an article in The Tax Adviser, a publication of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, which offered the mathematical proof that the Roth IRA was often a more favorable investment than a Traditional IRA.) The Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA) and subsequent tax legislation changed tax rates for all brackets and reduced tax rates for dividends and capital gains. After these tax law changes, I incorporated the changes into the analysis of the Roth versus the Traditional IRA. The Roth was still preferable in most situations, although the advantage of the Roth was not quite as great as before JGTRRA. However, our country is currently facing unprecedented financial challenges, and I would not be surprised to see the government intend to reduce our tax rates any time soon. And, if the tax rates on dividends and capital gains, or even the ordinary tax rates increase, the Roth’s advantage will be even greater.

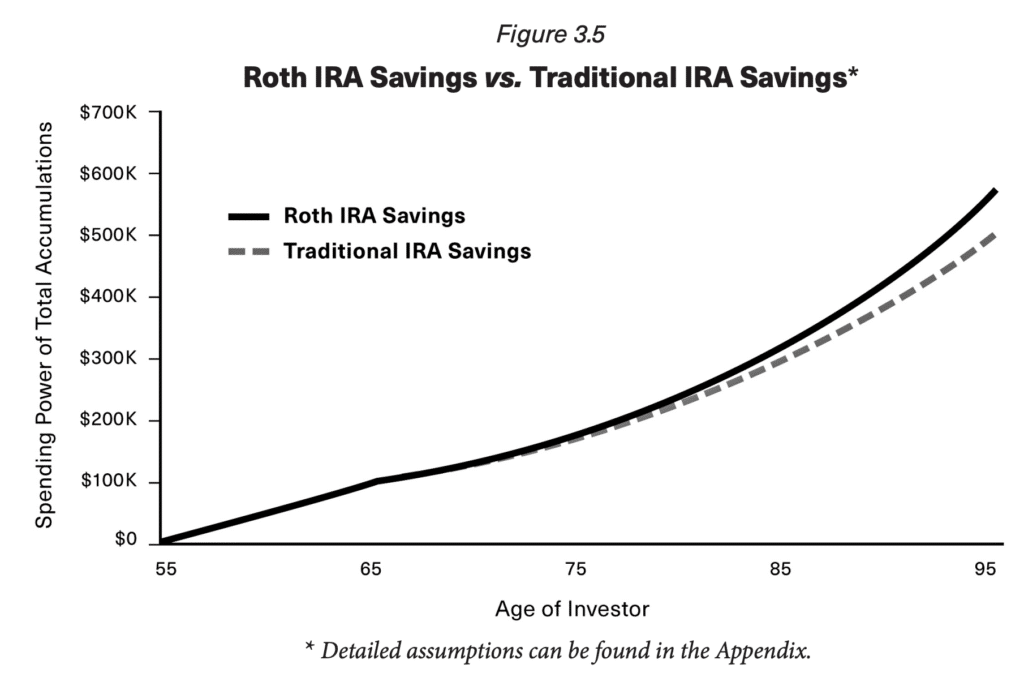

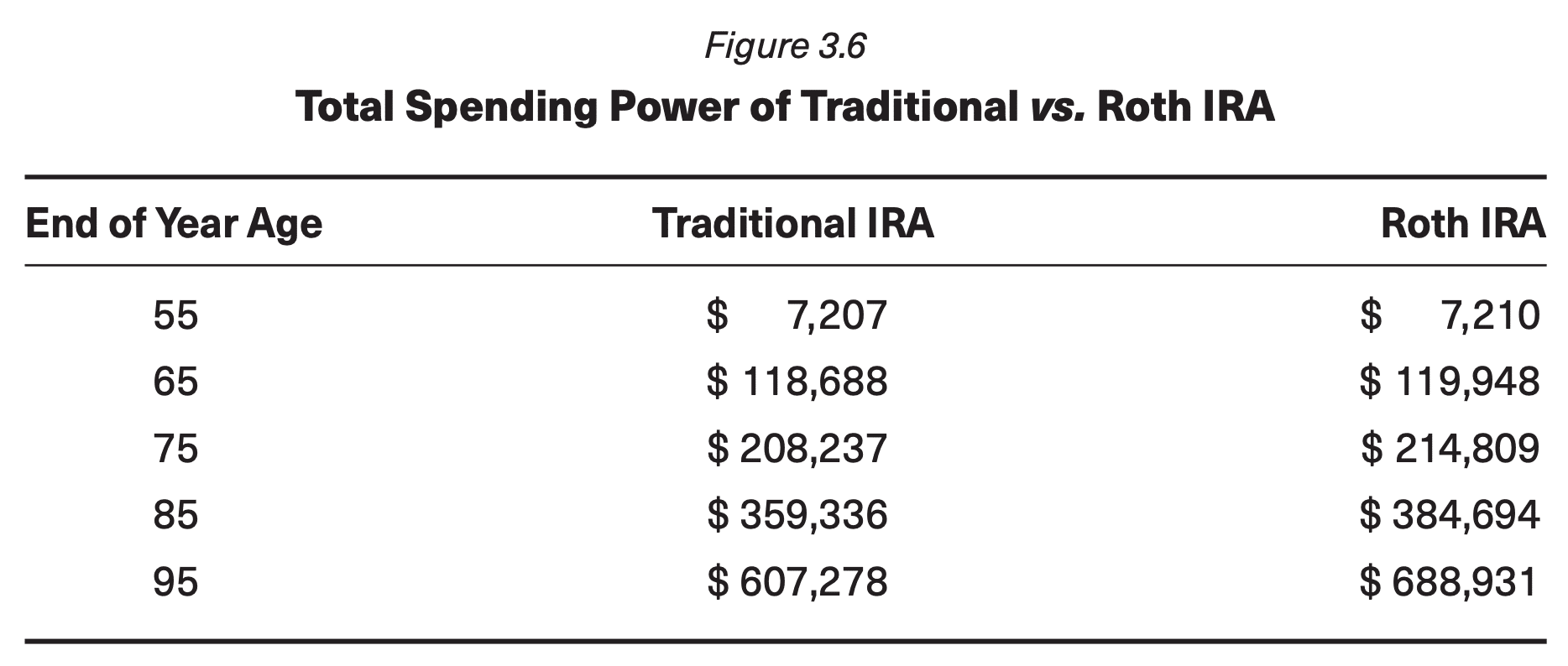

Figure 3.5 shows the value to the owner of contributing to a Roth IRA versus a regular deductible IRA measured in purchasing power.

The amounts reflected in the figure show that saving in the Roth IRA is always more favorable than saving in the Traditional IRA, even if the contributions are made for a relatively small number of years. If tax rates become higher in the future, or if a higher rate of return is achieved, the overall Roth IRA advantage will be larger. Given a long-time horizon (such as when monies are passed to succeeding generations), the Roth IRA advantage becomes even bigger. The spending power of these methods at selected times is shown in Figure 3.6 on page 70.

The very limited (11-year) contribution period and very conservative (6%) rate of return. In short, it demonstrates that, even with minimal contributions, shorter time frames, and very conservative rates of return, the Roth IRA will still provide more purchasing power than a Traditional IRA.

The Effect of Lower Tax Brackets in Retirement

I will usually recommend the Traditional IRA over a Roth IRA if you drop to a lower tax bracket after retiring and have a relatively short investment time horizon. Under these circumstances, the value of a Traditional deductible IRA could exceed the benefits of the Roth IRA. It will be to your advantage to take the high tax deduction for your contribution and then, upon retirement, withdraw that money at the lower tax rate.

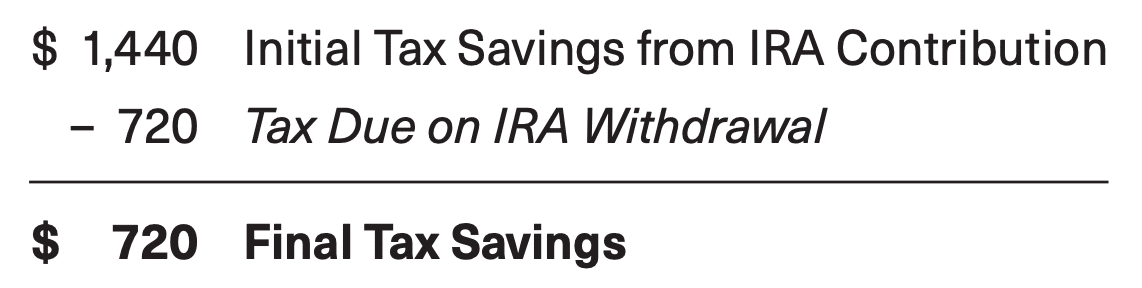

For example, if you are in the 24% tax bracket when you are working and make a $6,000 tax-deductible IRA contribution, you save $1,440 in federal income taxes. Then, when you retire, your tax bracket drops to 12%. Let’s assume that the Traditional IRA had no investment growth—an unrealistic assumption for a taxpayer who chooses to invest his IRA in a certificate of deposit which, at the time of writing, paid historically low interest rates. If he makes a withdrawal of $6,000 from the Traditional IRA, he will pay only $720 in tax—for a savings of $720.

If you drop to a lower tax bracket after retiring and have a short investment time horizon, I usually recommend the Traditional IRA or 403(b) over a Roth IRA or 403(b).

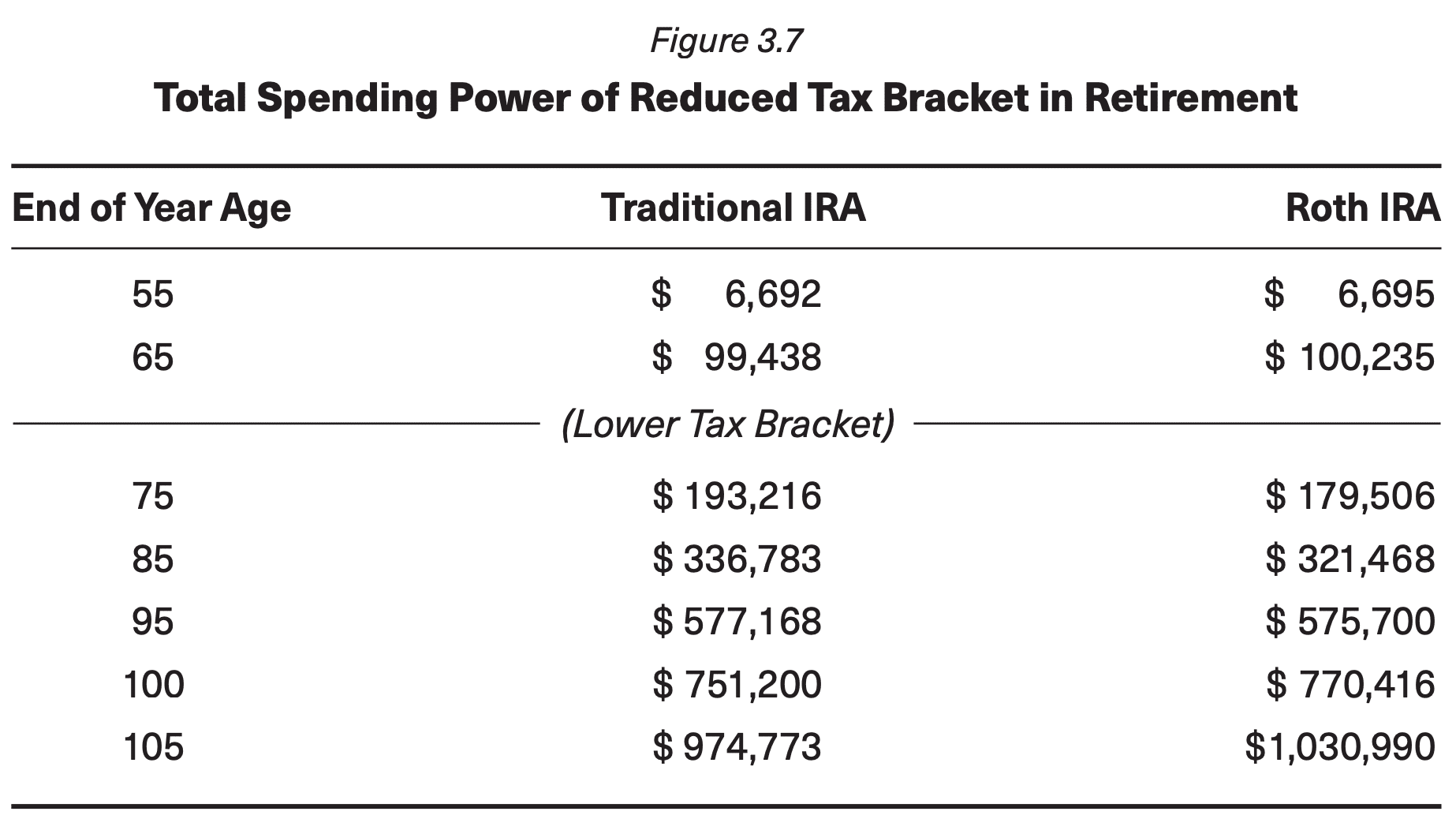

The advantage diminishes over time. So I ran the analysis again, starting with the same assumptions as in the previous example, except that, beginning at age 66, the ordinary income tax bracket is reduced from 24% to 12%.

The spending power of these methods at selected times is shown in Figure 3.7 on the next page. You can see that, under this particular set of circumstances, the Traditional IRA would be more beneficial to you during your lifetime. Note, however, that the Roth offers more spending power from age 100 on. Of course, most people will not survive until 100, but we show the analysis to point out that even facing a reduced tax bracket, the Roth IRA will become more valuable with time—an advantage for your heirs.

If you anticipate that your retirement tax bracket will always remain lower than your current tax rate and that your IRA will be depleted during your lifetime, I usually recommend that you use a Traditional deductible IRA over the Roth IRA.

Unfortunately, once the RMD rules take effect at age 72 for tax-deferred IRAs and retirement plans, many individuals find that they are required to withdraw so much money from their IRAs that their tax rate is just as high as their pre-retirement tax rate. And, when their RMDs are added to their Social Security income, some taxpayers find themselves in a higher tax bracket than when they were working. For these people, a Roth IRA contribution is usually preferable to a Traditional IRA.

These numbers demonstrate that even with a significant tax-bracket disadvantage, the Roth IRA can become preferable with a long enough time horizon. Furthermore, when you consider the additional estate planning advantages, the relative worth of the Roth IRA becomes more significant. (Please see Chapter 15 for a more detailed discussion of making a Roth conversion in a higher tax bracket when you will likely be in a lower tax bracket after retirement.)

Roth IRA vs Traditional IRA: Key Takeaways

When evaluating a Roth IRA vs Traditional IRA, the long-term impact of taxes often matters more than the upfront deduction. While Traditional IRAs can provide immediate tax savings, Roth IRAs offer the potential for tax-free growth and tax-free withdrawals, which may significantly increase purchasing power over time. As shown in the analysis above, factors such as future tax rates, investment time horizon, required minimum distributions, and estate planning goals all play a role in determining which account is more advantageous. Understanding these differences is essential when building a retirement strategy designed to last.

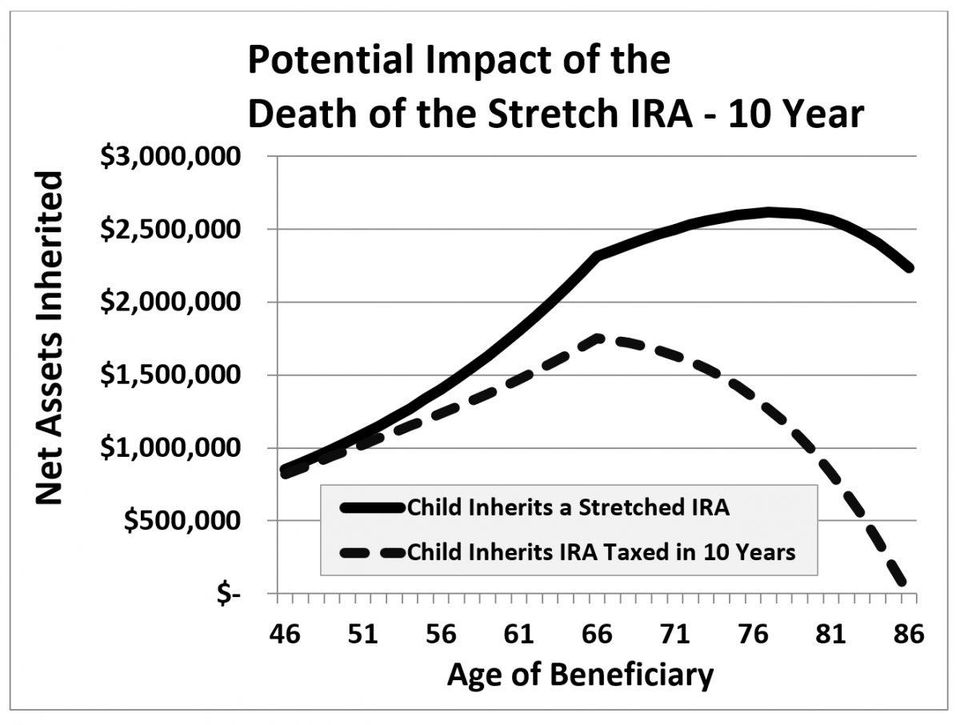

As I have written about, this is personal to me. I was hoping that distributions from my Roth IRA and IRA would be “stretched” over the life of my daughter and maybe grandchildren. It could make a difference of well over a million dollars to my family.

As I have written about, this is personal to me. I was hoping that distributions from my Roth IRA and IRA would be “stretched” over the life of my daughter and maybe grandchildren. It could make a difference of well over a million dollars to my family. The House is scheduled to vote on Thursday, May 23, 2019, on the SECURE ACT. Then, it will be in the Senate’s court to vote on RESA. Then the House and Senate will need to reconcile the differences between the bills. Experts, including us, think a compromise will be found and that the “stretch IRA” as we know it, will be gone, dealing a severe blow to IRA and retirement plan owners who were hoping their heirs would be able to continue deferring the distributions on their inherited IRAs and retirement plans for decades.

The House is scheduled to vote on Thursday, May 23, 2019, on the SECURE ACT. Then, it will be in the Senate’s court to vote on RESA. Then the House and Senate will need to reconcile the differences between the bills. Experts, including us, think a compromise will be found and that the “stretch IRA” as we know it, will be gone, dealing a severe blow to IRA and retirement plan owners who were hoping their heirs would be able to continue deferring the distributions on their inherited IRAs and retirement plans for decades.